Earth's record holders

How ice cores aid in scientific discovery

If the world’s glaciers could talk, what stories could they tell? What lessons could they impart?

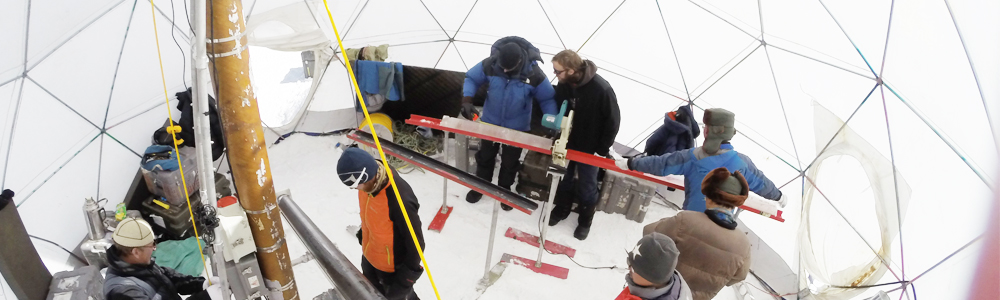

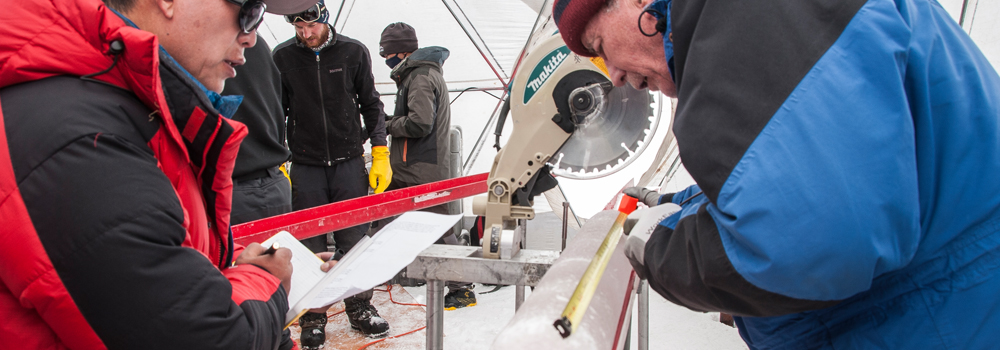

In many ways, that’s what the research scientists at The Ohio State University’s Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center unearth when they drill ice cores from all over the world.

Ice preserves everything present in the atmosphere at the time of a snowfall, allowing researchers to study chemical records preserved in the ice and reconstruct past climates at all latitudes on the planet, said Lonnie Thompson, senior research scientist at the Byrd Center and a Distinguished University Professor in Ohio State’s School of Earth Sciences.

“Glaciers serve both as indicators of climate change in that they respond to warming or cooling by advancing or retreating, and also as recorders of the past, both of climate and environment,” he said.

Long and valuable paleoclimate histories can be extracted from ice cores, said Ellen Mosley-Thompson, Distinguished University Professor in the Department of Geography and Director of the Byrd Center.

The center houses more than 7,000 one-meter-long sections of ice cores extracted from the Arctic and the South Pole and many locations in between, including the tropics and subtropics. The cores have been collected from 16 countries on five continents over the last 30 years.

The Ohio State ice core research team has documented more than 34 “firsts.” Among their top five achievements are: recovering the first tropical ice core record of the “Little Ice Age” (1550 to 1880 A.D.); discovering the oldest ice found outside the polar regions; retrieving the first ice core records of the Asian and South American monsoons; discovering glacial stage ice (more than 20,000 years old) in the Tropics; and documenting and determining the causes of the loss of high mountain glacier archives around the world.

The frozen archive will allow ongoing research as scientific tools continue to evolve, Mosley-Thompson said.

The research scientists discussed what lessons the ice cores can share and how they are used by climate researchers around the world to deepen understanding of our world.

What do ice cores reveal?

- Past temperatures, measured through isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen in the ice, and past precipitation recorded in the annual layers of ice.

- The history of atmospheric chemistry. “We can look at how the dust and salts carried in the atmosphere have changed through time. The concentrations and types of atmospheric aerosols can provide evidence of droughts,” Thompson said.

- The anthropogenic impact of industrial and agricultural activity on the environment and other processes recorded by trace elements that may indicate the onset of the Anthropocene, or the age of mankind.

- The evolution of microorganisms. “You have the potential of pulling information from ice cores on how bacteria have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years,” Thompson said. That’s useful because the life spans of bacteria are short, and such knowledge could help medical researchers understand why strains of bacteria evolve to become resistant to antibiotics.

- Changes in vegetation through pollen and plant fragments deposited with snow.

- Volcanic activity, revealed through the sulfates and gases archived in the layers.

- The role of greenhouse gases. “Ice is the best recorder of the past atmospheric composition because it contains bubbles that capture the atmosphere at the time when the snow compacts to become ice. We can look at the natural variability in carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide through time,” Thompson said.

Why do scientists need to know all that?

“The instrumental records that describe the Earth’s climate only go back about 150 years at best,” Thompson said. “And that’s too short a window … if you want to look at how the Earth’s climate system has changed in the past.”

Having the perspective of time is critical to understanding how the natural system has worked and how human activities are affecting it. Some of the Byrd Center’s ice cores date back tens of thousands of years, and studying them gives researchers a perspective that human history can’t provide, he said.

What do we know as a result of ice core research?

“We have found ice in the tropics that was deposited during the last Ice Age (more than 20,000 years ago),” Thompson said. “Up until in the 1990s, everyone, including us, didn’t believe you’d find ice that old on the mountaintops of the world. It gives us a global perspective on the climate during the last Ice Age.”

Some of the low-latitude ice cores also contain remains of plant and insects, and researchers can study the DNA to see how they have evolved.

“One of the beauties of ice is that it preserves anything and everything at the time the snow falls. Our limitation is just being able to read it properly,” Thompson said.

How else is this information helpful

Comparing the information learned from the ice cores to human history helps explain the role of climate, particularly droughts, in the rise and fall of civilizations.

Another field that researchers at the Byrd Center are studying is the long-term history of weather events caused by El Niños. They hope to discover the frequency of the extreme events and how they’ve changed through time.

“There are a lot of questions that can be addressed using this ice core archive,” said Thompson, who after 40 years in the field believes researchers have only scratched the surface of what they can learn from the ice cores.

Many of the techniques Thompson and other researchers are using could be applied in the future to study ice bodies on Mars and some of the moons of Jupiter.

“You have to understand how to read those records, but if you wanted to look for evidence of life on Mars, the best place to look would be in the ice,” Thompson said.