Recruiting your own immune system to fight cancer

Immuno-therapy offers new frontier in the fight against cancer

In 2015, former President Jimmy Carter was diagnosed with late stage melanoma, a form of skin cancer that had spread to his brain and other organs. For a number of reasons, traditional means of fighting it — surgery, chemotherapy — wouldn’t work. So doctors tried a more novel approach: immuno-oncology or immunotherapy.

Three months later, Carter’s tumors and skin cancer had vanished. And, based on past successes in immunotherapy, it is believed that the cancer cells weren’t coming back because his immune system had learned to stop them in their tracks.

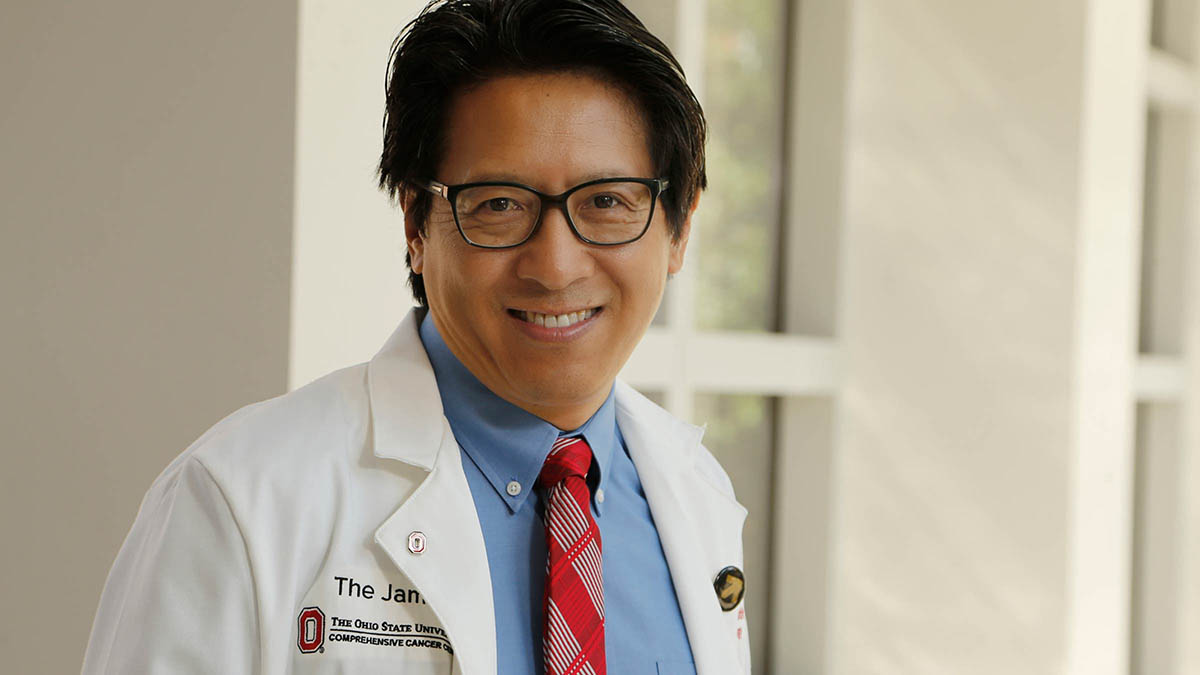

“We see patients like Jimmy Carter get effectively cured, and we get very excited,” said Dr. Zihai Li, PhD, the founding director of Ohio State’s Pelotonia Institute for Immuno-Oncology (PIIO). “We see it’s not science fiction anymore, that the dream we can eradicate cancer can be realized. The war can be won.”

Currently, however, only about 20% of cancer patients are able to use immunotherapy to fight cancer. But that number is rising. And Li aims to see the PIIO — which was established in 2019 — become a leader in this new pillar of cancer treatment.

Li recently spoke about the promise immunotherapy offers in the fight against cancer.

Immunotherapy truly represents the next frontier in the fight against cancer because it offers the promise of precision against an enemy that is by no means routine in its approach. Through innovative treatments such as CAR T-cell therapy, adoptive cell transfer, immune checkpoint blockers and cancer vaccines, immunotherapy serves as a first-line treatment in many cases.

But genetic, cellular or molecular changes in the body can cause cancer cells to grow, mutate, form tumors and also hide from the immune system to avoid attack. Immunotherapy activates the body’s immune system. It gives the immune system the ability to see and attack cancer cells, offering a less invasive treatment option than traditional therapies. Immunotherapy is specific, adaptive and functional, regardless of tissue type.

Another advantage of immunotherapy is that it can actually recognize something it’s seen in the past. So in the future, if the immune system sees the same enemy again, it can mount a far greater, more effective attack. This is called immunological memory; it’s the same thing we see in vaccines. Therefore, if immune-based therapy works, it usually has a long-lasting effect. In other words, there’s a chance for cancer to be cured in a person

But with only about 20% of patients benefiting from this treatment, we’ve got much more work to do. We need to figure out why 80% of patients don’t respond. We have to figure out exactly how tumors use the immune system against itself to not only survive but to thrive. And once we’ve found those answers, mechanistically, we need to work hard to translate our findings into therapies that will benefit not some, but all cancer patients.

I firmly believe that one day soon, cancers will effectively be treated by immunological means. It is not a question of “if” but for many cancers “when” immunotherapy will be the main treatment modality.

If you dial back the clock 15 years or so, we did not see much success. People didn’t think immunotherapy worked, and it felt hopeless.

But now it’s surpassing expectations, and there’s tremendous hope that indeed one day we could treat cancer like other chronic diseases, such as diabetes or hypertension. We have it but we can manage it. It’s a very exciting time.

To learn more about the successes and current endeavors of the Pelotonia Institute for Immuno-Oncology, check out its website.